Understanding Recommender Systems: Dynamic Content-Based Filtering

Recommender Systems are used extensively in industry for thousands of different services from product recommendation for giants like Amazon and Flipkart, music recommendation in Spotify, video recommendations in YouTube, movie recommendations by Netflix, etc. For any ML enthusiast, it's a must know.

Posted by :  Lokesh Kumar ✪ ✪ 15 min read.

Lokesh Kumar ✪ ✪ 15 min read.

Contents

- Introduction

- Outline of the Approach

- Item Feature Extraction

- Recommedation

- User Modelling

- Conclusion

Introduction

Recommendation systems have existed since time immemorial but just have taken a different form. In olden days, the economic activity was local and there weren’t any kind of Multi-National Companies which we see today. Buyers and sellers interacted closely with each other, due to which the sellers developed a mental map of the buyers and gave personal recommendations to their customers. Now, the buyers and sellers are separated by thousands of miles and to fill the vacuum, we have the computer-based recommendation systems.

These algorithms assist the user to navigate through the plethora of information that’s available in the open web, by filtering the necessary information based on the user’s preference and interests. This also adds a touch of personalization which increases user experience many folds. Considering so many advantages, many tech giants and researchers have devoted a considerable amount of time in their lives to understand and develop efficient recommender algorithms. In this post, we will begin by understanding simple, effective and widely used recommender algorithm, Content-Based Filtering.

Outline

In this post, we will consider the problem of books recommendation and solve them with the help of content-based filtering. Here we have a set of items and we must rank items based on user preferences. This calls for representing both items and user preferences in numerical form to carry out our computation. We can use any feature extraction to get an effective representation of each of our products.

Ok, now we have the feature representations of each of the items. To give a head start, say the user reads a single book, say book $b_i$. The recommendation algorithm uses a similarity metric to compute the similarity between book $b_i$ and all other books features in our corpus. Then the recommendation is straightforward, just recommend most relevant books according to the chosen similarity metric.

A very important step we missed above is to model the user. A user’s interests are generally complex and can change dynamically. To model the user’s behaviour, (i.e) to find what’s interesting to the user, we need feedback from the user. So we will look into types of feedback both explicit (asking the user to rate the recommendation) and implicit (by observing his behaviour). We will construct a feature vector which represents the user preferences (which changes dynamically) and use the same method used above to compute recommendations which dynamically keep up with users interests.

Item Feature Extraction

As the name of the algorithm suggests, we must analyse the content of each item/document and effectively extract features from it. There are several ways to representing the text documents, but we will use a simple yet effective method, $vector-space\ model$. In the vector space model, a document $D$ is represented as a fixed $m$ dimensional vector, where each dimension represents a distinct word (or a n-gram of words) in the collection of documents. The $i^{th}$ entry in the document’s feature vector is $w_i$ which represents the weight of the word representing the $i^{th}$ position. The word assigned for the $i^{th}$ position is $t_i$ (for more general version, think of it as an entity which can be a word or combination of words). It’s indicative of the importance of $t_i$ in the feature representation. If in the document, word $t_i$ is not present, the $w_i=0$. How to calculate $w_i$s?

$w_i$s are calculated using $tf-idf$ scheme. This can be expanded as Term Frequency and Inverse Document Frequency method. As you can see it consists of two parts, term frequency and inverse document frequency. So, let’s reveal the $tf-idf$ equation.

In , $tf_i$ is the number of occurrences of word $t_i$ in document $D$, $n$ is the total number of documents in our corpus. $df_i$ is the number of documents where word $t_i$ appears at least once. Ok, why is the equation structured the way it is?

The two main characteristics of text documents are leveraged to justify $tf-idf$ equation ,

- More the number of times a word appears in a document, more it can influence the topics that the document represents. $(tf_i)$

- More number of documents the word appears in the collection, more poorly it discriminates between the documents. $(log(n/df_i))$

Let’s take an example and understand this method.

Consider $4$ books whose contents are represented as a list below. (pardon me for a single line books XD) Books and documents are used interchangeably thereafter.

# corpus[0] is the first book

# corpus[3] is the fourth book

corpus = [

'This is the first book.',

'This book is the second book.',

'And this is the third one.',

'Is this the first book?',

]

Now let’s calculate the counts of different words present in the corpus (the list of all our books/documents)

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

count_vectorizer = CountVectorizer()

X = count_vectorizer.fit_transform(corpus)

# X is the matrix of counts

# to get the set of words in our documents

print(count_vectorizer.get_feature_names())

Output:

['and', 'document', 'first', 'is', 'one', 'second', 'the', 'third', 'this']

We have $9$ distinct words in the set of 4 documents. For each word and in each document we can calculate the term frequency $(tf)$ and the inverse document frequency $(idf)$. Lets constraint our analysis to the first document and its easy to extend the analysis to all the other documents. Below shown is the number of words of the vocabulary is present in the first document.

{

'and': 0,

'document': 1,

'first': 1,

'is': 1,

'one': 0,

'second': 0,

'the': 1,

'third': 0,

'this': 1

}

The above dictionary gives the term frequency values of all the words in the corpus for the first document. For calculating the inverse document frequency, we need to know the number of times the words occur in all other documents. Let me display the dictionary which holds a list for each word, where each entry in that list represents whether that word is present in the corresponding document (represented by its index position in the list).

{

'and': [0, 0, 1, 0],

'document': [1, 1, 0, 1],

'first': [1, 0, 0, 1],

'is': [1, 1, 1, 1],

'one': [0, 0, 1, 0],

'second': [0, 1, 0, 0],

'the': [1, 1, 1, 1],

'third': [0, 0, 1, 0],

'this': [1, 1, 1, 1]

}

For example, take the word first, which holds the list $[1,0,0,1]$. This means that word first is present in first and the fourth document. Now document frequency is straightforward to calculate. $df_i$ is the number of document word $w_i$ appears = sum of all the numbers in each list. Here’s the python implementation of tf-idf mechanism for better clarity.

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

import numpy as np

corpus = [

'This is the first document.',

'This document is the second document.',

'And this is the third one.',

'Is this the first document?',

]

num_documents=len(corpus)

count_vectorizer = CountVectorizer()

X = count_vectorizer.fit_transform(corpus)

X = X.toarray()

dfi=np.sum(X>0, axis=0)

# TFIDF features for the first document (corpus[0])

# also note the difference in the formula

tfidf=X[0,:]*(np.log((num_documents+1)/(dfi+1))+1)

# normalized TFIDF features

tfidf = tfidf/np.linalg.norm(tfidf)

# print the tfidf feature vector for first document

print(tfidf)

Output:

[0.0, 0.469, 0.580, 0.384, 0.0, 0.0, 0.384, 0.0, 0.384]

Note the formula used to calculate the $tf-idf$ features is a bit different as compared to . The expression used in the above program is

The effect of adding 1 to the $idf$ in the equation above is that terms with zero $idf$, (i.e.), terms that occur in all documents in the corpus, will not be entirely ignored. But, if this confuses you, you can proceed and use .

Ok, now we have $tf-idf$ feature vectors for all our documents in the corpus. We have successfully extracted a numerical representation of the documents which can be used in our recommender system. In our dummy example, each document is represented by a vector $\in \mathbb{R}^9$ where $9$ is the number of words in our vocabulary. Let’s move to the next section a much more exciting one, Recommendation !!

Recommendation

We will now jump right into building a simple recommender system. Our approach as given in Outline is as follows. We have a numerical representation of all the documents in our corpus. We will use a similarity metric that can provide us with how similar the document feature vectors are. There are many metrics out there which measure the similarity between two vectors. We will use the well known metric the cosine similarity.

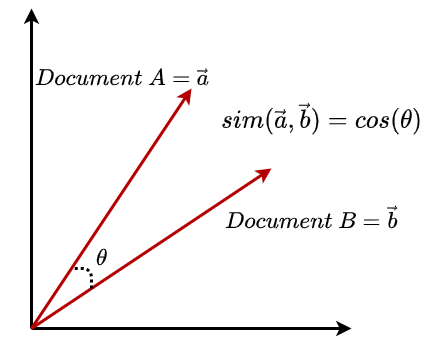

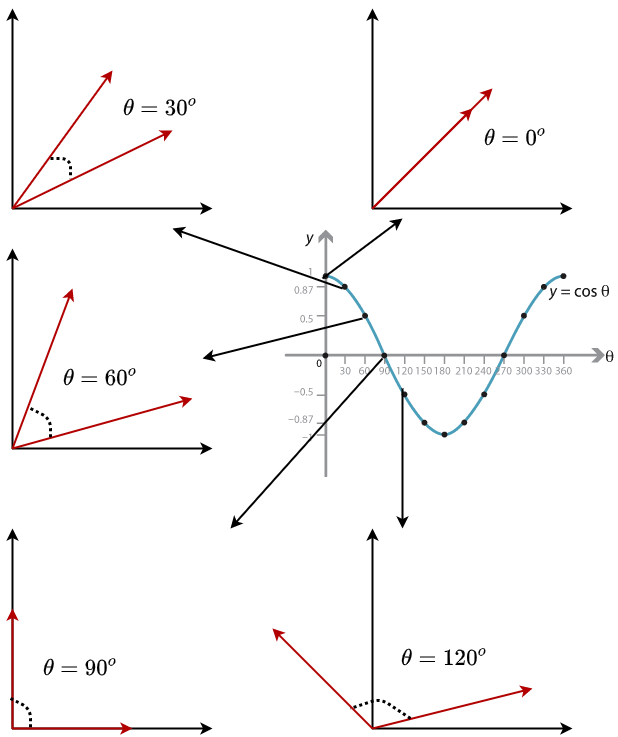

Cosine similarity of two vectors $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ is the cosine of the angle made by these vectors. From basic linear algebra,

where $\theta$ is the angle between $\vec{a}, \vec{b}$.

Why does cosine similarity make sense? As all the vectors are normalized to the unit norm, the following image makes it clear as to why it is intuitive. When the vectors are nearby, it makes the cosine similarity high, and as the vectors move apart ($\theta$ increases) similarity of vectors decrease.

The algorithm recommends the documents in the descending order of cosine similarity calculated between the $tfidf$ vectors of the documents.

Let’s look into the python code to understand more clearly.

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import linear_kernel

# books['authors'] is the list of description of each books we have

# we calculate the tfidf vectors of book authors

tf = TfidfVectorizer(analyzer='word', stop_words='english')

tfidf_matrix = tf.fit_transform(books['authors'])

# cosine similarity matrix

# cosine_sim[i][j] = cosine_similarity(tfidf[book i],tfidf[book j])

cosine_sim = linear_kernel(tfidf_matrix, tfidf_matrix)

Now we have all the pairwise cosine similarities in the matrix cosine_sim. Given any book, we can recommend similar books based on its similarity scores with other documents.

Note: I’m showing only important parts of code, for complete code go to Kaggle

# Function that get book recommendations based on the cosine similarity score of book authors

def authors_recommendations(title):

# get the book index

idx = indices[title]

# extract the book's similarity scores with other books

# sort them in decreasing order

sim_scores = list(enumerate(cosine_sim[idx]))

sim_scores = sorted(sim_scores, key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

# Take the first 20 book (other than the current book) and recommend

sim_scores = sim_scores[1:21]

book_indices = [i[0] for i in sim_scores]

# return the titles of the books

return titles.iloc[book_indices]

User Modelling

Till now, what we have done is, we have taken an item and recommended similar items from the corpus. How will a typical user behave when he enters your book site? He looks into many books, read some books, just bounce over some books, ignores others etc. This is a complicated behaviour, and cannot be modelled as we did in the previous sections. Moreover, if he is a regular visitor, his interests can change over time depending on his interaction with others, ongoing socio-political conditions etc. If your recommendation system needs to be relevant, it needs to adapt to the user’s changing preferences and always recommend consistent books in line with the user’s interests. This applies to all the fields which use recommender systems.

Modelling users is possible only if you have feedback from users. Feedback can be divided into two broad classes Explicit Feedback and Implicit Feedback.

Explicit feedback requires users to provide a certain rating by evaluating the documents which the user might not always be interested. Implicit feedback is the user’s interest inferred by observing the user’s actions, which is convenient for the user but difficult to interpret and analyse algorithmically.

Explicit feedback might not be a good choice because users may have to rate the items which they may be reluctant to do so, in the first place. Moreover, their ratings generally expire quickly. This means that the user’s interests are dynamic and just because he rated a book well doesn’t mean that he would always be reading similar books for the rest of his life. So it’s advantageous to learn user model from implicit feedback (observing user actions).

Another issue to tackle is the availability of negative examples. Say a user reads a book for a considerable amount of time. This is a strong indication that the user is interested in the book (positive example). Users ignoring the links to the documents or reading a document for a short span can be seen as a hint that he may not be interested. There is no strong evidence whatsoever to assert the same because he could have ignored the link to look at it later or haven’t noticed at all. He could have read documents for a short duration because it could be similar to other documents he has seen previously, but still, him being interested in the topic. Therefore including potential negative examples can end up making modelling the user very much difficult, so we must model the user only with sure positive examples.

Ok, now that we understood the basics of feedback based user modelling in recommender systems, we can discuss one simple way to model the user who is navigating your book store website. Each user is represented by a vector $P_t$ of dimension equal to that of the document $tfidf$ features dimension. Initially, when the user visits for the first time, you have no clue as to what the user’s interests are. So the user profile $P_0$ is empty (full of zeros). When the interacts with the article for a considerable amount fo time, then the update equation is,

where $F_D$ is the $tfidf$ feature vector of the document $D$ which the user interacted. The value of $\beta$ represents the relative importance of a document to the user. It can be determined using explicit feedback by asking the user to rate the document when he tries to exit the book. It can also be modelled using implicit feedback. For example, the recommender system Slider set $\beta = -3$ if the user deleted the document or rated poorly after reading, set to $0.5$ if the user just reads the article. Setting $\beta=1$ can perform well in many cases.

$\alpha$ is the forgetting factor. It determines how the user’s previous interests and interactions with the recommender system diminish with time. So by definition $\alpha \in [0,1]$. The lower the alpha, the more rapidly the user interests ‘forget’ about the past and modify his interests dynamically with his present actions. If $\alpha=0$, the recommendations are based completely on the current book the user last interacted with (with complete disregard to his past actions).

Conclusion

To develop more competitive recommender systems some factors which can be considered in the modelling can be:

-

Similarity between the document feature vector and the user profile vector as constructed from .

-

Novelty of a document which can be determined by the existence of information in a document which is new to the user

-

Proximity of the document, can be applied when there is a graph structure or an ordered relation among the documents. In the case of web-page recommendation, the webpages are arranged in a graph and the number of links separating the two websites gives a distance interpretation.

This completes the holistic coverage of content-based filtering for recommendation systems. Please engage in comments if you would like to. The next topic in this series is Collaborative filtering, Hybrid Recommendation methods, Multi-Arm Bandits based recommendation which inturn covers Graph and Networked Bandits, Visual deep recommendation, etc.